Last year we ran an article about Vampire Weekend’s Modern Vampires of the City. I basically just went song-by-song and tried to explain some of the more potentially obscure references and how I thought the songs fit into the larger thematic arc of the album. You can still read that piece, here, on the old buffaBLOG (from the “before times” in the “long, long ago.”)

That article was pretty well received and some people said that it was nice to have some extra context in which to enjoy the songs, even if most of it was just pure speculation and interpretation on my part.

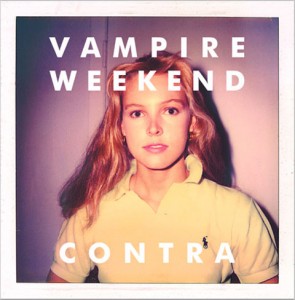

So, in anticipation of Vampire Weekend’s upcoming show at the Outer Harbor on Monday, I’ve made some comments below on the rest of the band’s catalog, which includes all of the songs from their self-titled debut album and follow-up, Contra.

Pick and choose from your favorite songs below or read the whole thing if you just can’t get enough of my pedantic parsing out of Ezra Koenig’s lyrics.

Vampire Weekend (2008)

1. “Mansard Roof”

A “mansard roof” is… well, it’s this. You’ve probably seen these throughout the northeastern United States (and there are several in the Elmwood/Allen area of Buffalo). The scene on the first track of the first Vampire Weekend album is a bit more coastal though as we have a reference to “salty eaves,” probably placing us somewhere between New York and Cape Cod.

The second verse refers to the defeat of the Argentine Fleet by the United Kingdom during the Falklands War of 1982. If we’re to take any meaning from this, it might be the relative absurdity of the United Kingdom continuing to defend its imperial conquests well beyond the point that it continued to exist as an actual “empire.”

If you’re looking for recurring themes on the first Vampire Weekend album, check here: nautical scenery, the 1980’s, and old moneyed interests pretentiously clinging to their pretenses.

2. “Oxford Comma”

An “oxford comma” is the comma that comes before the “and” in a list of three or more items. This is the example that is traditionally used in grammar classes:

I have 100 tons of steel, 50 tons of iron, and coal.

That last comma there is the “oxford comma” and the reason given for its necessity is that, without it, you get the following sentence:

I have 100 tons of steel, 50 tons of iron and coal.

In this second sentence, there could potentially be some ambiguity about whether the speaker has both 50 tons of iron and coal, whereas in the first sentence, it was clear that the speaker had 50 tons of iron and an unspecified amount of coal.

But… “why would you lie about how much coal you have? Why would you lie about something dumb like that?”

Good question Ezra! Ergo: “who gives a fuck about an oxford comma?”

Again, we’re dealing with pretension for pretension’s sake, where traditions are upheld, not necessarily because they make the most sense, but because it’s a way for a well-educated establishment to keep itself feeling established. (The actual debate over the necessity of the Oxford Comma is a fierce fray, which I will not enter here, but several well-respected style books disagree as to its usage.)

Ultimately, Koenig seems to be saying that rather than having a hard and fast rule about these things, maybe we should just use our judgment to get to the essential “truth” of what it is we’re actually trying to say. You know, like Lil’ Jon.

3. “A-Punk”

A-Punk tells a story about a girl named Johanna. She’s in New York City and she takes an heirloom silver ring from “His Honor’s” finger, which she had previously seen in Sloan-Kettering hospital in Manhattan (an excellent cancer treatment facility, which I visited when my grandmother was treated there for multiple myeloma). His Honor then takes off for New Mexico while Johanna stays in Manhattan and “the ring” ends up split between the song’s narrator and “the bottom of the sea.”

These are pretty inscrutable lyrics, but I’ve always imagined they might be a reference to Dylan’s 1966 classic, “Visions of Johanna,” (written while he was still living in Manhattan, himself) which is similarly non sequitur. The last two lines of Dylan’s song: “the harmonicas play the skeleton keys and the rain, and these visions of Johanna are all that remain,” almost seem as if they could have served as inspiration for “A-Punk,” which references a harmonica, a dead body, rain, and a girl named Johanna.

4. “Cape Cod Kwassa Kwassa”

Kwassa Kwassa is an African dance rhythm that became popular in the 80’s and Cape Cod is, of course, the home of the Mayflower, the Kennedys and the spiritual epicenter of traditional American white privilege.

The use of Kwassa Kwassa in this song earned the band some accusations of cultural appropriation back when the album first came out, but those accusations never really stuck, probably because the use of an African dance rhythm in close juxtaposition to traditional white stereotypes seemed to pretty clearly be a self-aware jab at cultural appropriation in the first place.

The other references in the song are to fashion and music that might allow someone to (only vapidly) lay claim to being “multicultural” (Louis Vuitton, Bennetton, reggaeton, Peter Gabriel). It’s basically a painting of people who might consider themselves rather world-savvy but can’t help seeming a little oblivious when viewed in larger perspective.

5. “M79”

The M79 is a bus in New York City that can take you across Central Park, connecting the Upper West Side to the Upper East Side. (There are also references to other forms of New York transportation in the song with the “pollination yellow cab” and the “coronation rickshaw grab.”) The idea of “connecting” one place to another also comes up later on the song via the suggestion that one could “charm their away across the Khyber Pass,” which connects Afghanistan to Pakistan.

References to “French kids,” “Buddha,” and “bleeding madras” serve up more, somewhat disparate, foreign touch points that paint a vague scene of the cultural diversity of New York. It’s not exactly clear what we’re necessarily doing with all of this culture, but there seems to be a reoccurring concern (via the “racist dreams you should not have” and not wanting to seem “so callous”) with finding the proper balance between appreciation and appropriation.

6. “Campus”

This song is a relatively straightforward collegiate tryst.

“Kefir” is a milk product native to Eastern Europe and a “keffiyeh” is a traditional Middle Eastern headdress, two words which seem to be combined in a lyric here both for their coincidental similarity and for yet another example of foreign cultures (here, literally) clashing.

My favorite part of this song is the line: “How am I supposed to pretend/I never want to see you again?” Which can be read either as two separate sentiments, (he can’t pretend AND he doesn’t want to see him/her again) or as a single sentiment (he can’t pretend THAT he doesn’t want to see him/her again).

Given the lesson of “Oxford Comma,” we should probably just go with whichever reading seems to “tell the truth.”

7. “Bryn”

Honestly, I really don’t have much to say about this song. I’ve never found it to be particularly interesting, lyrically or musically. I think if all of the Vampire Weekend songs crash in the mountains and they have to eat one of their own to stay alive, it should be “Bryn.”

8. “One (Blake’s Got a New Face)”

Blake seems to be yet another example of someone seeking a “new face” by becoming more culturally aware. However, that person is self-conscious of the degree to which they may come off as ignorant in the beginning (pretending like you understand the difference between “English Breakfast” and “Darjeeling” tea) or haughty in the end (“nastiness causing your doom” as you recoil in “absolute horror” at the prospect of your “collegiate grief leaving you dowdy in sweatshirts.”)

9. “I Stand Corrected”

Again, not much to say here. This song is pretty self-descriptive. He stands corrected.

10. “Walcott”

As the legend goes, while at Columbia, Ezra Koenig started filming an amateur movie called “Vampire Weekend” about a man named Walcott who needs to go to Cape Cod to warn the citizens of an impending vampire attack.

The song, “Walcott,” is mostly a fun take on the plot of this abandoned film where the narrator implores Walcott to “get out of Cape Cod” while name-dropping several local towns: Mystic Seaport, Hyannis Port, Wellfleet, and Provincetown. (And the “bears out in Provincetown” refers to its reputation as a homosexual enclave.)

It might not be too much of a stretch to think that the idea here is that the denizens of Cape Cod (previously painted in a not-altogether-flattering light earlier on the album) aren’t particularly worth saving from vampires.

11. “The Kids Don’t Stand a Chance”

The last song on the first Vampire Weekend album seems to be a reckoning with the album’s concern over what exactly someone should do after they’ve been lucky enough to be well-educated and introduced to a world outside of the typical American microcosm.

The first instinct of some people (and probably people like Ezra Koenig) might be to reject opportunities that more obviously lead to material wealth in favor of some more “noble” or “interesting” work. The problem is when the “pin-striped men of morning” come to dance, their “pure-Egyptian cotton” and “forty-million dollars” is probably going to look a little too good to resist. Even someone that didn’t initially “like the business at first glance” might change their mind after feeling how “soft” that Egyptian cotton pillow really feels.

Hence, “the kids don’t stand a chance.” They’re either going end up as vacuous slaves to capitalism or impoverished artist-types who secretly envy those same vacuous slaves to capitalism.

Contra (2010)

1. “Horchata”

The first track on the second Vampire Weekend album starts out with more relatively obscure foreign cultural references: a “horchata” (a Spanish drink made from various nuts and grains), a balaclava, an aranciata. These references come off as whimsical at first but things end up turning darker than most anything else on Vampire Weekend’s first album.

When Koenig sings: “Years go by and hearts start to harden, those palms and firs that grew in your garden,” we start to see the transition toward his focus on the passage of time and aging that ended up being fully realized on Modern Vampires. Those “lips and teeth that ask how my day went” suggests that those “feelings you thought you’d forgotten” are probably only getting further and further away.

2. “White Sky”

“White Sky” seems to describe a couple walking through “the middle of Manhattan,” including a stop by a clothing store (Julia standing on “a little piece of carpet, a pair of mirrors” and turning into “a thousand little Julias” while trying on clothes) and the Museum of Modern Art.

Koenig’s concerns about the attitudes of the privileged New York elite are still on display here when he admonishes “the pride and envy” of people who hoard art rather than put it on display for everyone to see and then imagines a pair of “Wolfords” (which I now understand to be very expensive tights, only through some research on my part) in a “ball up on the sink” in a Manhattan apartment building.

That such things are basically disposable to some people could certainly be a feeling that “all comes at once” in rather overwhelming fashion.

3. “Holiday”

“Holiday” has a similar trajectory as “Horchata” insofar as it starts off seeming light and playful and takes a darker turn three-quarters of the way through the song.

The bridge imagines the word “bombs” blown up into 96-point Futura (the typeface in which “Vampire Weekend” is written on all three of their albums),which is a pretty ominous word to equate with the well-recognized font used for the name of your band. That and the following reference to an “AK in a yellowy day-glo display” seem to suggest that the “holiday” the narrator is longing for might be from a slightly more menacing situation than a stressful office job.

4. “California English”

There’s a lot going on here lyrically but most of it seems to describe the lifestyle of a girl jet-setting from England to California, the fast-paced exhaustion of which is underlined by Koenig’s sped up vocal delivery. The unnamed main character seems to be torn between England (a “freezing flat,” a “stack of A-Zs”, and “freezing wind in your face”) and California (“sunburned scalps,” “dying in LA,” and unfinished condos) and this seems to have left her somewhat lacking in identity.

This song also (along with “I Think Ur a Contra”) gives the album its title through the lyric: “Contra Costa [a county in California, also ‘opposite coast’ in Latin], contra mundum [‘against the world’ in Latin], contradict what I say,” indicating that the conflict and opposition invoked through the album’s title can come in a variety of flavors (geographical, personal, all-encompassing, etc.)

5. “Taxi Cab”

The concern over class and status and, more specifically, the correct amount of class and status that one should actively seek to project onto the world, comes to the forefront on “Taxi Cab,” perhaps more than on any other Vampire Weekend song.

The best example of this conflict in their entire catalog might be: “when the taxi doors opened wide, I pretended I was horrified, by the uniformed clothes outside, and the courtyard gate.”

This seems to recognize that as much as people have traditionally put on pretenses to seem as though they have more class than they actually do, we’ve reached a point (in American culture at least) where being the type of person to have butlers and gated properties is a potential source of shame. Many people (at least in the current 20s-30s generation) seem to find more pride (or at least more “authenticity”) in a middle classman that’s had to fight for what they’ve earned.

As such, you can imagine why one might have to “pretend to horrified” by the trappings of the upper class in order to maintain some imagined form of credibility.

6. “Run”

“Run” is mostly a pretty straightforward song about escaping from the mundaneness of everyday life, though it does have one fairly interesting line that’s only quietly tucked in toward the end of the song. “She said, ‘you know there’s nowhere left to go,’ but with her fund, it struck me that the two of us could run.” This suggests that the idealistic escape described throughout the song might only be possible because the girl in this situation just so happens to have access to hidden cache of inherited loot. Implicit in this is that “running” might not actually be an option for everybody.

7. “Cousins”

The lyrics to “Cousins” can largely come off seeming like nonsense, but there is probably some coded language here, which, If I had to guess, seems like it’s describing the way we tend to put a lot of importance on where we “come from,” whether it be our family, city, state or country of origin.

There are several references here to family, (“Dad was a risk taker, his was a shoe-maker”) and “heard codes in the melodies, you heeded the call, you were born with ten fingers and you’re gonna use em all,” seems to suggest that the son has chosen to be a musician. There’s also a reference to “accruing interest” due to one’s “birthright” and the “line that’s always running” between cousins, again, pointing to the entitlements that we inherent though merely being born and through no deliberate act of our own. “Turning your back on the bitter world” might be a natural reaction to feeling pigeonholed by the choices of prior generations.

8. “Giving Up the Gun”

“Giving Up the Gun” is another step in the direction of discussing the idea of getting older and deciding what we may or may not be willing to part ways with during that process. Here, “the gun” is symbolic of some obtained status (such as the power and spontaneity of youth) and giving it up in favor of an “old and rusty sword” would be an admission of defeat that your 17 year-old “wrists like steel” have “faded behind a brass charade.”

This is reinforced by the reference to a “Tokugawa smile” on a guitar player who has seemingly resisted “giving up the gun” by “failing to move an inch” in the “coming wave” of old age. This almost certainly refers to the Tokugawa shogunate, which was the last Japanese shogunate prior to the imperial Japanese government, which, literally, had to give up the [sho]“gun.”

9. “Diplomat’s Son”

“Diplomat’s Son” is probably my favorite Vampire Weekend song. It has such an odd air of mystery to it and weaves in and out of musical segments with a shifty alacrity like it’s sneaking around a house at midnight. I also love it because it’s one of the most directly narrative Vampire Weekend songs, while still remaining just vague enough (in a hazy nostalgia-driven sort of way) to keep itself open to interpretation. I’m not positive about this, but here’s how I see it.

The song is about a young man who, “in ’81,” has formed some sort of friendship with a “diplomat’s son,” which presumably places him in an old-guard family of importance; a status not shared by the narrator. Throughout the song, the narrator seems to be plotting a romantic tryst with the diplomat’s son, starting the song right off by thinking, “it’s not right, but it’s now or never, and if I wait could I ever forgive myself?” This is further supported by him thinking: “If I ever had a chance it’s now then, but I never had the feeling I could offer that to you.” Ultimately, he’s not looking for long-term relationship though as he makes it clear that “all I want to do is use, use you.”

As the song goes on, he seems to make his move on the “night when the moon glows yellow in the rip tide.” The scene is set with a “TV buzzing in the house,” the narrator “ducking out behind them,” with his “car keys hidden in the kitchen.” Rostam Batmanglij then appears on the bridge (perhaps, as the diplomat’s son) singing: “I know you’ll say I’m not doing it right, but this is how I want it,” before Ezra comes back on the track to make things a bit more explicit: “that night I smoked a joint with my best friend, we found ourselves in bed, when I woke up he was gone.”

The part that really ties this all together though is the last four lines laid over a suddenly chilly outro. The narrator finds himself looking out at “ice-cold water all around him” and begins losing feeling as he sees a car driving away “all black with diplomatic plates.” I suppose there’s several ways to read this, but I can’t think of a more compelling way to read it than that the diplomat himself found out his son had been fooling around with another man and decided to put an undiplomatic end to the relationship.

10. “I Think Ur a Contra”

“Contra,” aside from being part of a 1986 political scandal and an awesome 1988 Nintendo game (facts probably not lost on a band relatively fond of 80’s references) is also a Latin word, literally translating to “against.” I think you’re “an against” doesn’t really directly translate though, unless you take it to mean that the person accused of being a “contra” is merely “against,” in general, in that they’re on the other side of whatever you represent.

I take this to mean that pretty much all situations can, almost too easily, be boiled down to “pro” or “con,” and that this tendency to over simplify is inherent in the very language that we speak. There are no (commonly used, at least) Latin-prefixes for middle ground or nuanced positions. In that way, if you aren’t completely onboard with someone, you might as well be a “contra.” This seems to come up through the idea of not wanting to “choose sides” or “choose between two,” yet still somehow being forced to do so for want of it ever seeming like there are more than two sides or options.

Is it “good schools and friends with pools” or “rock and roll, complete control?” There’s probably a way to have both of those things, but if you’re with someone who seems to want one or the other more than you, they’ll probably feel like they’re contrary to you regardless. That might be how we end up with Koenig singing “don’t call me a contra, until you’ve tried,” possibly meaning, “don’t say I’m against what you want until you’ve tried to understand that it’s possible to have it both ways.”

Although, if a highly educated group of musicians can write a bunch of songs replete with obscure cultural references to form a financially successful rock band, maybe you can have it both ways, and the kids might stand a chance after all.